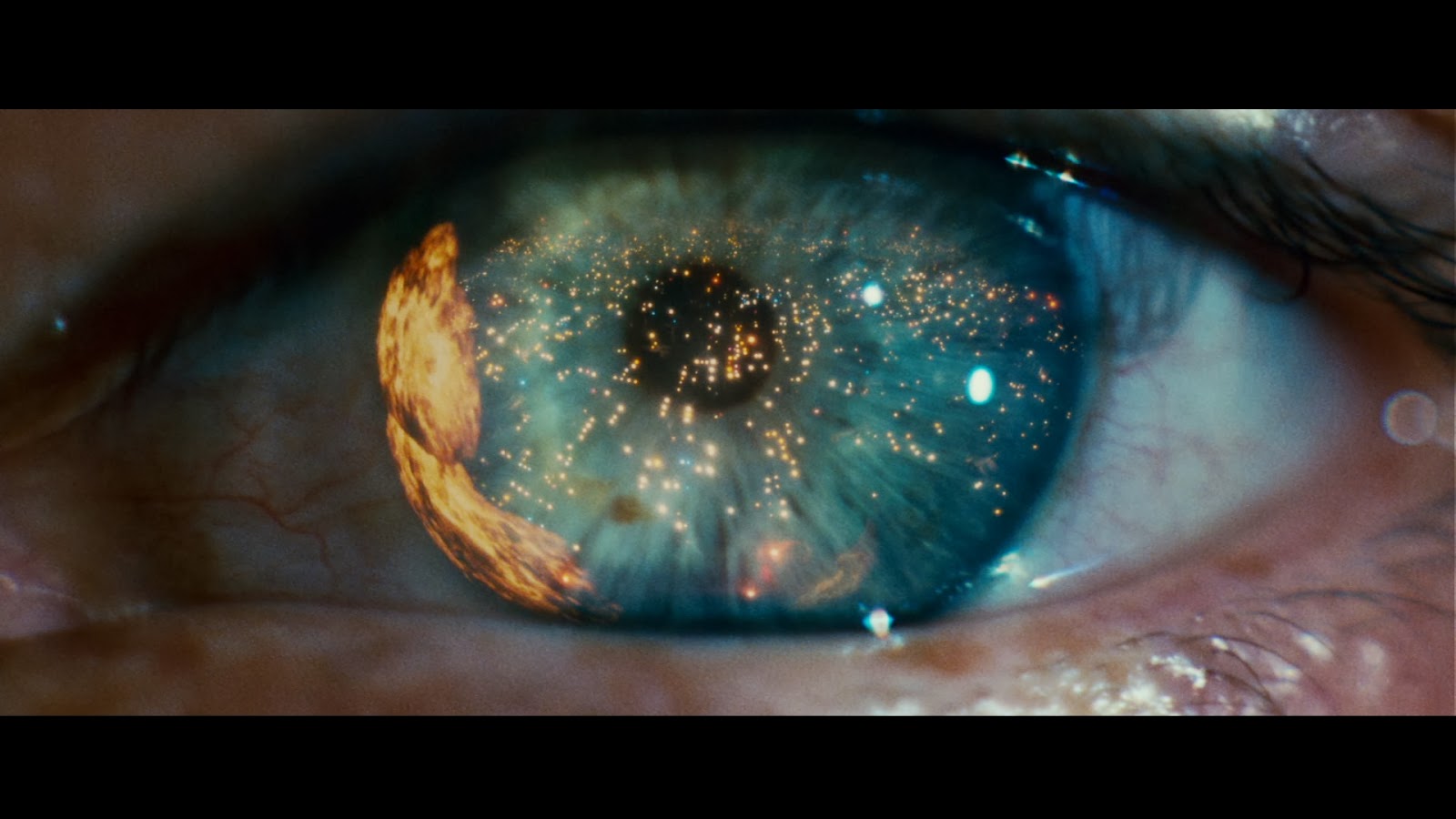

Anyways, Blade Runner: forerunner of the grimy dystopia, palpably atmospheric setting, haunting cinematography, deft performances from around the board, the most intact synthesized music to come out of the 80’s (see: minimalism) -- it has it all. More importantly, as has been well-established, Blade Runner is the poster-child of postmodernity in film. With its fusion of so many conflicting elements it’s easy to see why. Wet, muddled streets are crowded with transitory customers and dilapidated souls; above their heads, commercialism runs rampant with ads tracing the height of skyscrapers and zeppelins promoting off-world destinations; and even higher, the kings of industry like the Tyrell corporation with its regal ziggurat dominate the city scape. Yet these different classes are bound by perpetual deluge and by their confinement to an exasperated earth.

And this is merely the blending of social and economic locales. The film has merged countless other incongruities, especially its anachronistic treatment of genre and technology. In his essay, “Building Blade Runner,” Norman M. Klein details a few of these fused elements. He says, “the construction of the blade runner look is very revealing… it is tangibly an old memory remodeled, a movie based on an old movie set about city life.” Furthermore, he stresses the importance of nostalgia in the film, emphasizing that it “replaces social reality.” And he’s right. The movie re-introduces traditional items, like film noir of the thirties and forties with a femme fatale Rachel and a Bogartesque Deckard, all with the intent of establishing viewer comfort with a disconcerting world.

Klein also reiterates that other critics had chastised Blade Runner at the time of its release as being an example of “style over substance.” While I don’t think that the early eighties were yet accustomed to this reversal, whereas today we are well acquainted with style’s ability to become substance, the bottom line is that the movie is purposefully “insubstantial.” It eschews a complex plot for intricate philosophy and a setting that effectively replaces the need for plot. The film is meant to be distant and seemingly hollow. The people are meant to seem aimless. Klein says, “I see a world where no one has time or place to sit longer than a few minutes, where the streets are endlessly milling.” Herein lies another facet of the movie’s postmodernity. This is a stagnant earth. People that can progress are gone; those that remain are rushing around without cause and, in some cases like J.F. Sebastian and his disease, they wither away without hope of improvement. This is why Roy’s emotional effulgence at the end is so climatic. It is the most energetic and most emotional display in the movie -- there is rage and laughter and love and pain and excitement and fear, all poured into his primal howls.

So what is the purpose of this postmodernity in Blade Runner? Does it go beyond constructing a fictional, alternate reality of our world in which we must change our ways to avoid? Here’s where I’m going to get loftily conjectural as I also feel the need to further investigate postmodernity whenever I try and understand its function, something that is quite incorporeal as postmodernity prides itself on its purposelessness.

Anyways, I think (as of right now -- this opinion is bound to change upon the completion of this overly long post) that the purpose of postmodernity is to reach a sort of post-postmodernity. If the main tenets of modernism revolve around the ideas of progression and objective truth; and we understand postmodernity to be the subversion of such tenets; but we consider progression to be inevitable, though perhaps varied in its degree of improvement, because by default it is a byproduct of the passage of time; then postmodernity is just a means of more closely examining possibilities for potential progress, be it through fragmentation or another postmodern device, so that when the time comes to consciously move forward (and that time will come because it is inevitable) we (society) will have a stronger idea of the more advantageous routes to follow for progression.

If this is the case, Blade Runner becomes even more of a standard-bearer for postmodernity. As mentioned before, it is a future that we can watch in relative safety and a future that we will not have reached by its prescribed date. There are similarities between our world and their’s, but in the end it is more dissimilar than not: it is stagnant and paradoxical and thus purposeless (what is the point of being human if we’re less human than an artificial man?). Perhaps this movie serves as a bridge, like other postmodern works, to get us to back to a point of purpose -- that post-postmodernity. If the critics with their claims of “style over substance” are right in saying that this movie is meaningless because reality will not occur according to Blade Runner, then the viewer is now able to extract a purpose from the movie’s philosophies, perhaps discerning the movie as a warning that we should appreciate being human and that we should not squander that opportunity.

Does the movie explicitly reveal this intention? Not really. It elongates our growing destitution, and travels a much drearier path than this cheerful ascertainment -- not to mention its ambiguous resolution with three or four different version makes this determination debatable. And that’s why this movie will remain relevant (philosophically, of course! Obviously, the movie is relevant for its varied scifi progenitorship). On the surface it is seemingly meaningless, but underneath lies a murky pool where answers can be plucked and molded into resolutions, or alternatively crafted to counter such resolutions.

Does the movie explicitly reveal this intention? Not really. It elongates our growing destitution, and travels a much drearier path than this cheerful ascertainment -- not to mention its ambiguous resolution with three or four different version makes this determination debatable. And that’s why this movie will remain relevant (philosophically, of course! Obviously, the movie is relevant for its varied scifi progenitorship). On the surface it is seemingly meaningless, but underneath lies a murky pool where answers can be plucked and molded into resolutions, or alternatively crafted to counter such resolutions.

Lastly, I’m left questioning this movie’s place in the early 80’s. It seems antithetical to the affirmation of conservative values that we had discussed last week with E.T.. I find Blade Runner to be a counter argument directed at those growing values because the film rejects solidarity. Yes, the movie paints a crude rendition of an Asian take-over that probably would have affirmed certain political landscapes during that time, but it also paints capitalism in a negative picture with our industry having bled the world dry. That certainly doesn’t support the rhetoric of the Reagan-era. Moreover, this might explain its rather perverse representation of christianity, especially compared to E.T. In Blade Runner, man becomes God by creating new men and crafting new worlds, and these creations end up throwing down their God. Additionally, these creations that cast down their God are the most religious entities in the movie. Remember, Roy displays the most emotion of all and constantly retains his conscientiousness while Deckard is left helpless and bewildered with Ford at his finest. Also, add in the heavy-handed Christian motifs (dove, nail-in-the-hand) and the replicant really is your most devout character. How is a viewer to make sense of this artificial man being the most holy? Go-go postmodernity!

These rejections of Reagan-era policies aside, the movie does answer some of the cultural anxieties of that time, similar to E.T. of last week. Rather, it allows the viewer to determine a satisfying resolution of their own making, going back to that murky pool metaphor. The film channels American anxieties into a fictional world. As Klein touched on, “The bladerunner city, therefore is comforting in a strange way. We won’t live there. It is not our future. It is their future. But we will be allowed to visit.” No wonder Blade Runner fathered so many subsequent dystopias and post-apocalypses, even more prevalent today, with the genre's allure being its alleviation of cultural worries.

That was really strange to me that critics found that it was more style over substance. I thought that it had a good amount of substance to it while maintaining a combination of sci-fi and noir feeling. When I think of style over substance I think of Tarantino's Pulp Fiction or Kill Bill where style is really the more focal point of the movie. I will say though I'm a huge Tarantino fan and especially Kill Bill and Pulp Fiction.

ReplyDeleteYou mentioned that the humans are stagnant in their progress as human beings, I found that a really satisfying aspect of this future world where the humans have let their "progress" bleed the earth dry of all its resources and reached a point in which progress is no longer possible on Earth in the usual sense. Tyrell is the only person in the movie who seems capable of progress in this world. He is making replicants that are better and more human like and advancing his technology to an amazing degree. This makes it even more satisfying when he is killed by the replicants he created. He has elevated himself to a God and then he is killed by his "progress" and eliminated from a world that very clearly can't handle anymore human progress. Its like the replicants have taken over where nature left off before it was eliminated,except, being so human themselves this becomes a much more complicated message to decipher. It makes you wonder what would happen if the replicants were to slowly take the place of the humans who have lost hope and purpose in this bleak world, would they keep destroying it? If Roy is any representation of the majority of replicants that are left in space or wherever else, I would like to think they might do what I would consider the more human thing and try to reverse the damage.

ReplyDeleteIt's interesting that Klein, along with other critics, said that this movie was more style over substance. Although I can agree that style is quite important in this film, due to the postmodernism of it, I also think that it had quite a bit of substance. Cultural anxiety is presented throughout the movie and takes its form in a nuclear war and mass destruction. I think that along carries a lot of substance, especially during the time that this movie came out.

ReplyDeleteThis is terrific, Jack. You handle the postmodern aesthetic incredibly well--defining it nicely, incorporating the reading, and also raising the very valid issue of what post-post-modernity would look like, especially given that you're watching this definitively postmodern film an entire generation later. Having set that up, you could easily have delved into one of the deeper layers of the reading--the postscript at the end where Klein revisits his own essay a few years later, discussing the actuality of LA urban development and gentrification--a very different direction than the noirish, grimy but insubstantial city of the future that so fascinated designers.

ReplyDeleteI'm not sure why you're wanting to counter an argument that this film reflects Reagan-era values though. I don't know that anybody has made that argument. I agree, this film if anything critiques and subverts them. I don't know that anybody has argued otherwise. As a counter critique, that particular point would be much more fun to apply to the readings about ET and Rambo we've had--both of which to my mind also have a strong subversive streak. Anyway, well done!